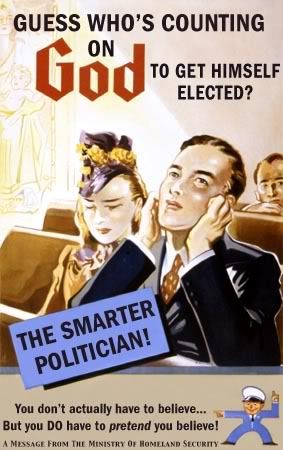

Family First is demanding that all Federal candidates declare whether they are now, or ever have been TEH GAY:

And everybody knows that gay values aren't Australian values, non? Everybody knows that as soon as you let one of those into Parliament, they'll immediately proceed to infect our beloved Christian democracy with TEH GAY. Santorum spreading everywhere. Before you know it, your 15-year old son is being sodomised with the rough end of a heroin-laced outcomes-based education, while being forced to watch lesbian witch porn on the Internet.

Fundies First: the gift that keeps on giving.

UPDATE: The backpedalling has begun already.

The Family First candidate in the far north Queensland seat of Leichhardt says voters have a right to know the sexual preference of all candidates contesting the federal election.

A report in today's Courier-Mail newspaper says Family First's Ben Jacobsen demanded that the Liberal candidate Charlie McKillop declare if she is gay.

Mr Jacobsen, who is against gay relationships, says he was not targeting Ms McKillop, but speaking generally about every candidate.

"Look I think this is a public office, this is a person that's going to represent Leichhardt in our House of Representatives," he said.

"I think the public have a right to know the values that you're going to pursue in Parliament." (ABC)

And everybody knows that gay values aren't Australian values, non? Everybody knows that as soon as you let one of those into Parliament, they'll immediately proceed to infect our beloved Christian democracy with TEH GAY. Santorum spreading everywhere. Before you know it, your 15-year old son is being sodomised with the rough end of a heroin-laced outcomes-based education, while being forced to watch lesbian witch porn on the Internet.

Fundies First: the gift that keeps on giving.

UPDATE: The backpedalling has begun already.